Mandy El-Sayegh

by Amie Corry

Reviews /

Exhibition

• 21.05.2019

Mandy El-Sayegh’s exhibition Cite Your Sources is a complex thing. Dialects, surfaces, skin, soap, sores, death, sex and Brexit jostle in heavy layers – streams of conscious and unconscious thought, stories, propositions and reflections. It is beguiling and angered, and it requires a bit of work from the viewer. Commissioned by the Chisenhale Gallery, London, the exhibition tackles ideas relating to psychoanalysis, postcolonial theory, inherited trauma, abstraction, language and its role in upholding social structures, and centrally, the body. What could feel abstruse is, however, tempered by a fleshiness, an explorative openness to mess and fracture that plays out throughout this work. It is academic yet candid, personal – her father’s calligraphy features – while political. The strength of Cite Your Sources is its wilful resistance to categorisation; I will not make this comfortable, El-Sayegh seems to say, because it is not and never has been.

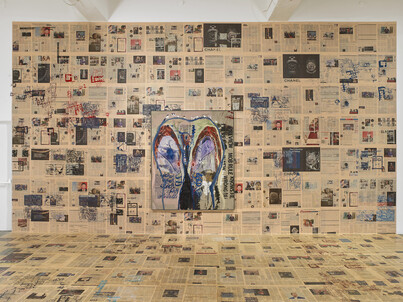

The walls of the single space are split FIG.1 – regular white cube in the larger section and the noisy installation Figured Ground (2019) in the other, in which pink – what is still commonly referred to as ‘flesh-’– toned pages of the Financial Times coat the gallery walls and floor FIG.2. On the white walls, six uniformly sized screenprints greet the viewer FIG.3. The first, Soft circuit #1 (2016), is an upscaled page from a 1980s electronics magazine. Dense English, littered with codes, accompanies diagrams of guitar tuner circuit boards. The text is overlaid with large sweeps of Arabic, on top of which, heavily foregrounded, is a grid made of tubes of a peach or tan-coloured plasticine material.

Soft circuit #1 is a good introduction to this show: the combination of forms is unsettling and tactile, the composition considered, while the title nods to the way we make sense of things through bodily language. The squishiness of the rubbery grid against the dry text highlights another disparity: between the science of the hard, right-angled electronics and its result, music. In the subsequent prints, the viewer encounters nineteenth-century medical diagrams (in this case, swollen syphilitic appendages), kitsch Victoriana imagery of a young white girl admiring her reflection, a Snickers wrapper recast with the words ‘Sidelined’ (a special NFL edition) and the Daily Mail logo. Amid these concrete forms, hazier passages of colour and sketched chunks of bodies emerge. These last are glimpsed, coming in and out of focus depending on the viewer’s distance from the work.

The final print, Niceday (2019), features a crudely drawn, silhouetted child’s head with rows of red squares filling the space usually taken up by the brain. The silhouette recalls the well-known face/vase figure-ground diagram used to illustrate Gestalt theory, although probably only if you are already aware of El-Sayegh’s interest in Gestalt. Developed in Berlin in the 1920s, the psychology looks at the way disparate elements – perhaps denoted here by the red squares – are perceived as meaningful wholes, greater than the sum of their parts. It is the fragments, however, that El-Sayegh is concerned with. More specifically, she seems to ask what happens when the Gestalt is made unavailable to you, or whether, in the case of the body, it is ever available, particularly if you are excluded from the dominant social and political culture. ‘I see the body arising as fragmented with free floating affects in all its absurdity’, the artist notes in an interview with the curator Ellen Greig.1

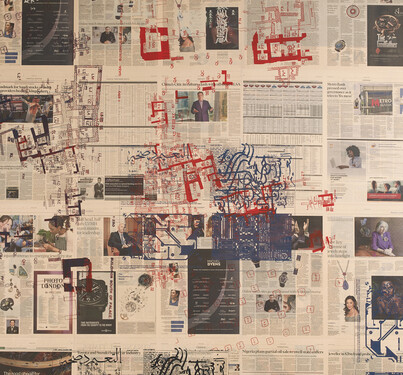

Flashes of just-recognisable body parts, continue in El-Sayegh’s large series of Net–Grid paintings FIG.4. Recalling raised-relief maps, the surfaces of the Net-Grids ripple and buckle beneath the weight of their matter – layers of glue and paint, studio rags, newspapers, and printed images of vulvas, arteries, Theresa May and victims of unknown disasters (a comment on the prominence of ‘corporealised brown bodies’ in the media). All this is contained, or trapped, beneath thin wobbly lines that criss-cross over the entire canvas surface. They present a sort of topography of contemporary visual culture: how it shimmies and darts, takes apart and desensitises.

El-Sayegh notes that as a student in London she felt locked out of the art historical narratives taught there: ‘I felt that there was a whole set of systems that I did not know, like a joke that I didn’t get’.2 In the Net-Grid paintings, she offers a rejoinder: the modernist grid is shakily recast, and, instead of a reclining nude or the heavy machismo of an Abstract Expressionist colour field, we are presented with something else, much harder to define. The argument slowly emerges that all imagery – particularly that of the body – is a form of abstraction, as elements are isolated and decontextualised.

News and words are everywhere in this show, but – like the floating body parts in the Net-Grids – they speak strongly of fracture. Although the Financial Times pages are intact, the text and layouts are carved up with other lettering and imagery FIG.5. Some of the news pages repeat, which interrupts the illusion of a steadily moving stream of news. These duplications feel like glitches or mistakes – more words and less said. El-Sayegh’s father, whose calligraphy appears over the FT pages, is from Gaza, and the artist has spoken of the silencing of trauma in Palestine, both literally in terms of her father never discussing his past, and as inherited, the pain relating more to the hypocrisy or wilful blindness of the West. For El-Sayegh, probing these silences is an indirect call to arms: ‘bodily fissures should be celebrated, as opposed to covered’, she has said, ‘in order to serve as a confrontational power to engender action and discussion’.3

Taken together, the Financial Times’s litany of Theresa Mays, Brexit machinations and actors in Omega watches starts to feel increasingly absurd. This encroaching feeling is reinforced in El-Sayegh’s series of slender steel and glass vitrines, which are positioned in the middle of the gallery space and filled with arrangements of readymade and sculptural objects. The vitrines offer, at first glance, a bit of relief, something solid to hold onto. But this quickly turns to sand: porn and Beatrix Potter, broken glass, rubber pumps, soap that metamorphoses into flesh, orifices and cuts FIG.6, Israeli military operations, passports, American Apparel adverts. The vitrines are brilliant and lift the show, leaving the viewer to ponder the madness of it all, while trying to shake the frightening feeling that the way we look and speak and process is far more complex than we might ever want to believe.