Negotiating borders

by Sarah Bolwell

Reviews /

Exhibition

• 07.11.2019

Positioned at the intersection of three aggressive world powers – Russia, China and Japan – Korea has, over the centuries, been the battleground for conflicts between other nations. The division of the Korean Peninsula was first proposed in the political discussions that would ultimately lead to the Russo-Japanese war of 1904–05. Such a division was not realised until sixty years later, when the United States and the Soviet Union shared out territorial spoils after the Second World War. The creation of North Korea and South Korea has had a devastating and lasting impact on the citizens of the peninsula and world politics; it divided families, friends and businesses, and it perpetuates nuclear hostility as the last vestige of the Cold War. Negotiating Borders at the Korean Cultural Centre UK, London (KCCUK), explores the invisible Military Demarcation Line (MDL) that splits Korea along the 38th parallel, and the very visible impact of its enforcement. The joy of this exhibition on a potentially bleak subject is the revelation that the borders of the Demilitarised Zone (DMZ) that surrounds the MDL are more permeable than might at first be presumed. ‘Border’ is a slippery word, and one that the exhibition fully interrogates. The springboard for the presentation is the physical frontier – the 248-kilometre-long and 4-kilometre-wide strip of land that divides the Korean Peninsula topographically – but through this thoughtful presentation the viewer comes to understand equally the non-visual dimensions of border – the social, political and cultural.

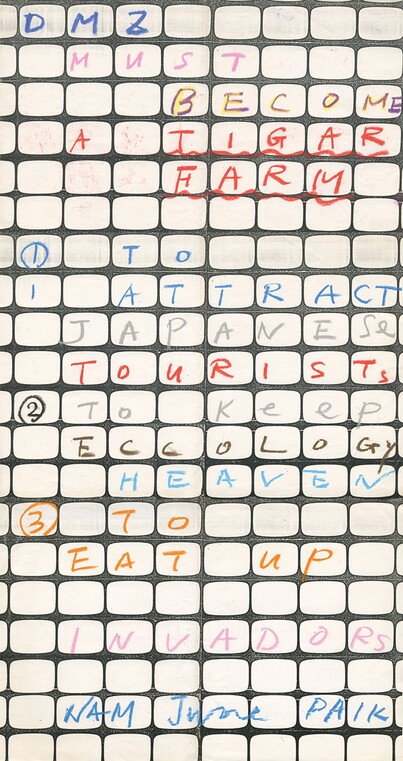

The exhibition is organised by the Real DMZ Project, a research collective founded in 2012 in Cheorwon, a small town at the geographic centre of the Korean Peninsula, where the ceasefire agreement that ended the Korean War was signed on 27th July 1953.1 The collective took its name from the title of an exhibition, Project DMZ, staged in New York in 1988, which displayed artist proposals for a non-military and anti-political DMZ, some of which are included as archival material in the current exhibition. Nam June Paik proposed the land become a tiger park FIG.1 in order: ‘1. To attract Japanese tourists’; ‘2. To keep eccology [sic] heaven’; and ‘3. To eat up invadors [sic]’. Paik’s first reason may seem a little flippant, indicative perhaps of his disenchantment with the progress towards a unified Korea and with Japan as an historic aggressor. The second is a positive outcome of the DMZ in that since its instigation, the DMZ has developed into a rich ecosystem that houses globally endangered plant and animal species.2 The third may have been a nod to the ‘invadors’ that descended on Seoul that year, when it hosted the Olympic Games (whose official motto was ‘harmony and progress’), but it is perhaps better understood as a comment on the international interventions in Korean politics over the centuries that have resulted in the tragic current situation. Negotiating Borders tackles these paradoxes head on.

This is the first exhibition by the Real DMZ Project to combine documentary research and visual arts on a large scale. Displaying commissioned works of art alongside photographs and paraphernalia from the DMZ Archive, this format successfully slows the pace at which we consume as viewers. The DMZ Archive – examples from which are on view here for the first time – comprises photographs dating back to the 1950s, paraphernalia associated with the collective’s various projects and the Botanical Archive, drawings of plants from the Korean National Arboretum found in the DMZ FIG.2. The archive’s function is to make memory material. In the case of collective memory – of accurately representing it and constructing it – the process of selection in itself can be dangerous. The curators of the exhibition have carefully negotiated this, choosing to include a range of materials, both military and domestic, human and vegetal. As such, the message of the exhibition is one of concentrated and meticulous study. There are few spectacular works in the exhibition that encourage Instagramming, indeed, probably the least successful work in the exhibition is a large collection of military blankets arranged on the floor under barbed wire, by Minouk Lim. This ‘site-specific’ piece is presumably intended to evoke the spectacle of death, but in the context of a commercial art world that is currently saturated with large installations, it falls somewhat flat.

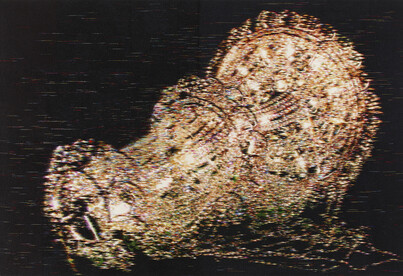

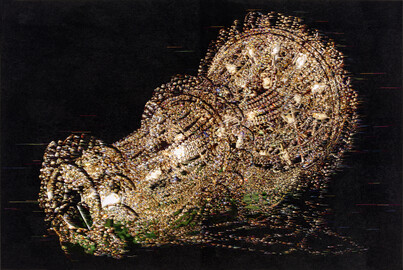

The reading requirement of Negotiating Borders is not limited to documentation. Two large wall-mounted tapestries by Kyungah Ham, each depicting a glittering fallen chandelier FIG.3, demand interrogation, as the thick sturdiness of the embroidered panels is at odds with the blurry twinkling of the broken glass FIG.4. Part of Ham’s ongoing ‘Embroidery Project’, the chandeliers illuminate the invisible hard labour of the embroiderers. A wall text relates how Ham sent her designs from South Korea to craftspeople in North Korea to weave; to make this forbidden connection with Koreans north of the border, text and images had to be sent via Chinese and Russian intermediaries, and via unconventional means as explained in her listed ‘mediums’ for the piece, which include ‘middle man’, ‘smuggling’, ‘bribe’, ‘tension’, ‘anxiety’, ‘censorship’ and ‘ideology’.

Blow Up is a collection of photographs by Seung Woo Back originally taken in North Korea in 2001 FIG.5. Heavily monitored by North Korean officials during his trip, Back felt the resulting images were pedestrian and unrevealing. Several years later the artist revisited the images and reproduced details from the original photographs, enlarging previously unnoticed moments and characters. A civilian out for a jog who had previously blended into the background takes on new poignancy as a reminder of the similarities of daily life north and south of the border. Crucially, it taps in to the exhibition’s ideology that revisiting the same issue might generate different results.

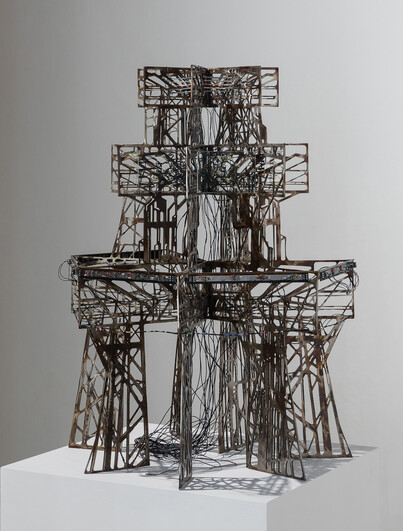

In Study for Aubade V FIG.6, Lee Bul presents a scale model for a piece to be made from melted barbed wire from guard posts in the DMZ. In its repurposing of materials from abandoned buildings and military structures, Lee’s work strives to demystify the concept of the border: in fully understanding the composition of the border – physically as well as politically – we are better placed to deconstruct it. Lee’s practice is theory-led, with the works she has made in response to the DMZ specifically, she meticulously welds together elements of Derridean philosophy and utopianism with her personal experience of growing up in a military dictatorship and understanding of the physical landscape of Korea.

Ultimately the sort of measured negotiation encapsulated in Lee’s work, and the exhibition as a whole, is of vital importance to the unity of Korean people moving forward. The approach of Korean artists to the DMZ has evolved over the years: seemingly wild suggestions of tiger parks have given way to environmentally-savvy proposals for biodegradable dwellings FIG.7. But Paik’s original suggestion to deter ‘invadors’ still resonates in modern-day Korea, whose history is defined by intervention from outside powers. This is a Korean-curated exhibition of Korean artists that successfully explores a Korean issue. The Real DMZ intends with its next iteration to look to the global artistic community. It is uncertain how effective this approach will prove, as with every new generation, the more connectivity there is globally, the less physical and cultural connection there is between those either side of the 38th parallel. The central aporia of the official motto of the Seoul 1988 Games ‘harmony and progress’ is that the further that these two nations progress in their different agendas, the less harmony seems a likely outcome.