The Lives and Loves of Images: Biennale für aktuelle Fotografie 2020

by Lisa Stein

Reviews /

Exhibition

• 16.04.2020

In his essay ‘Le musée imaginaire’ (1947) André Malraux argued that the museum ‘imposed on the spectator a wholly new attitude towards the work of art’.1 Isolated from their context, paintings and sculptures were exhibited alongside works of conflicting styles, encouraging the ‘practice of pitting works of art against each other’, and it was through this comparison that the nature and quality of individual works was criticised. Malraux referred to this as the ‘intellectualization’ of art, a process accelerated by the emergence of photography: ‘For the last hundred years’, Malraux noted, ‘art history has been the history of that which can be photographed’.2 Although reproduction suited his idea of the ‘museum without walls’, in which all major works of art would be represented, Malraux acknowledged that the photograph of a work of art was one step closer to its abstraction.

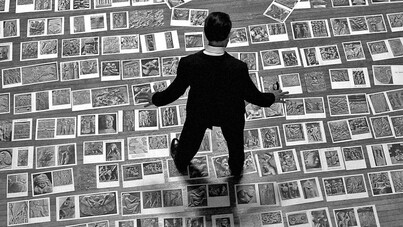

Malraux’s passion for the tactility of the art object and his despair over its gradual dematerialisation is the subject of the video work Malraux’s Shoes by Dennis Adams FIG.1, on display in one of six exhibitions that make up the 2020 Biennale für aktuelle Fotografie, Germany’s largest curated photography festival.3 Based on a well-known photograph of Malraux standing in his study with the plates of Le Musée Imaginaire de la Sculpture Mondiale (1953) laid out on the floor before him, the forty-two minute black-and-white film shows Malraux – played by Adams – walking among the spreads of his book, switching between a contemplative interior monologue and explosive outbursts: ‘Fuck Sherrie Levine! I was fucking stealing statues in Cambodia!’4 His anachronistic comparison – having died in 1974 Malraux would not have been familiar with the American artist – is particularly apt in the context of a biennial devoted to photography, since Levine’s project of photographing reproductions of photographs by Walker Evans is itself a ‘philosophical reflection on photography as an inherently reproductive medium, with a fraught relation to art and the notion of the “original”’.5 Levine’s copy of Evans’s portrait of Allie May Burroughs, the wife of a sharecropper he photographed in 1936, is on display in another of the biennial's six exhibitions.

What would Malraux have made of Levine’s photograph, a faithful reproduction of what was considered by contemporary viewers as a document rather than a work of art? What is the significance, at a time when the photograph itself is ‘dematerialising’, of displaying prints? And how have the possibilities afforded by technology and new media influenced the way we think about photography as an art form? The ambivalent status of a medium that has ‘come to symbolize the extremes of contemporary society’6 is explored in The Lives and Loves of Images, the second edition of the biennial born out of what was previously known as the Fotofestival Mannheim-Ludwigshafen-Heidelberg. Launched in 2005 across six cultural institutions in Southern Germany, the festival was reconceived in 2017. The first instalment of the new biennial, entitled Farewell Photography, explored how the digitisation of photography influenced the appearance and accelerated the distribution of images, and changed the relationship between photographer, subject and viewer.7 This year’s iteration, curated by David Campany, presents contemporary photography alongside images from the past century to place the ‘issues we face now in longer historical continuity’.8

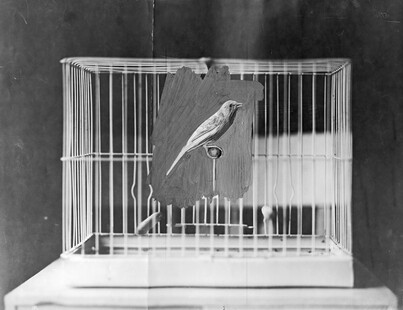

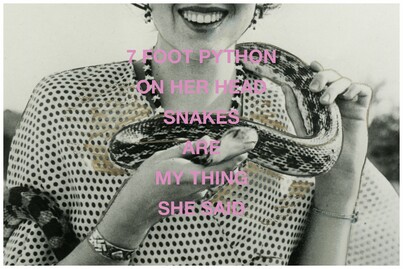

Anxiety over the accelerated distribution of an increasing number of photographs is nothing new,9 neither – as an exhibition at the Heidelberger Kunstverein demonstrates – is their susceptibility to manipulation. Yesterday’s News Today presents historical press photographs alongside series by contemporary artists that incorporate and rework archival imagery. Sebastian Riemer’s enlarged press photographs reveal how errors were eliminated and unwanted details blanked out in a time before Photoshop. Fine pencil marks and subtle strokes of grey paint that would have gone unnoticed in the pages of a newspaper are affectionately preserved in these large-scale prints FIG.2. Clare Strand’s black-and-white photographs of girls and women holding snakes, which the artist sourced from magazines, instructional books and press archives, are overlaid with the text that was written on or attached to the back of these images FIG.3. Dark and bizarre phrases such as ‘girl plays with snake, ache ache with snake, snake plays with girl, ache ache girl snake’ and ‘7 foot python on her head, snakes are my things she said’ are reminiscent of the ‘alt text’ used within HTML code and the phrases or buzzwords we type into Google.

Arranged on glass tables according to specific categories such as ‘camping’, ‘theft’ or ‘beauty queen’, the archival news photographs demonstrate the correlative relationship between image and text, which undermine each other as authoritative systems of communication. Revealed by additional mirrored shelves beneath the images, various notes made by news and picture editors remind us that whether we encounter photographs in newspapers or on our Twitter feeds, they are usually subordinate to text that is composed by an individual or institution. In museums and galleries photographs are accompanied by captions and wall labels. In his introduction to the catalogue, Campany asks what happens when we are confronted by images without words. ‘Are we prepared to simply look and think for ourselves? What do we need to know in order to look? [. . .] What kind of understanding comes simply from looking?’10 In The Lives and Loves of Images ‘words are kept to minimum’: individual works are numbered, and corresponding artists and titles are listed on sheets available at each exhibition. As our eye naturally darts to the space outside individual images seeking a caption, we suddenly become aware of the extent to which we rely on additional information when faced with a photograph.

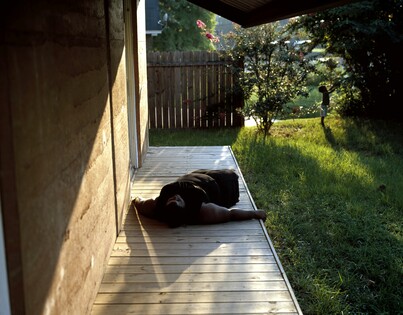

Campany’s approach is most successful in the highlight of the biennial, Walker Evans Revisited at the Kunsthalle Mannheim. The exhibition combines some thirty photographs by Evans – displayed on white columns scattered throughout two gallery spaces like trees in a forest – with work by eighteen contemporary photographers hung on the surrounding walls, revealing the key to Evans’s enduring relevance. His photographs of anonymous and vernacular culture speak to a pleasure that comes from simply looking, a feeling that is reflected both in the contemporary work on display and in innumerable photographs in circulation today. The first room includes artists who continue Evans’s manner of capturing everyday life such as RaMell Ross, who documents Black lives in the American South FIG.4, and Lisa Kerezi, whose images of hand-drawn or hand-painted signs and lettering FIG.5 are almost interchangeable with Evans’s photographs of similar subjects.

The second room includes responses to particular images and projects by Evans. For AfterSherrieLevine.com FIG.6 Michael Mandiberg scanned Levine’s series of photographs after Evans and published them online to further ‘facilitate their dissemination as a comment on how we come to know information in this burgeoning digital age’.11 For her 2014 series Reparation, Julia Curtin reconfigured the dress worn by Burroughs in Evans’s portrait by stitching together details of the garment from his photographs FIG.7. Curtin’s haunting, beautiful photographs embody the many ‘extremes’ Campany attributes to photography in his introduction to the catalogue, the many ‘lives’ it lives: ‘it is deeply personal, and yet thoroughly public. Freeing at times, yet also limited and limiting. Expressive, yet culturally dominant. Pleasurable, but worrying'.10

The biennale’s title is borrowed from W.J.T. Mitchell’s book on the historical, cross-cultural implications of the power of images, What Do Pictures Want?, in which the author shifts the location of desire from the producers and consumers of images to the images themselves.13 Mitchell’s idea of attributing agency to images speaks to our anxiety about the photograph, particularly the digital-borne image, which, highly susceptible to manipulation and appropriation, can take on a life of its own. But although Campany warns that we should be suspicious of the power, manipulations and distractions of photography, the often unintended or unpredictable ‘life’ of the digital image is not thoroughly explored. This biennial feels like a missed opportunity to present photography outside of its relationship to art. There a disconnect between these images and how we encounter the majority of photographs today, not in museums or newspapers but on social media. What about the photograph used in the meme, which has replaced the cartoon as a vehicle for social criticism? What about deep-fake technology and the algorithms designed to recognise these kinds of images? What about the ‘lives’ of non-human photographs, such as those taken on Mars? What about medical imaging and clinical representation in photography?

Although the work included directly references the digital image, the exhibition All Art is Photography presents the medium as always in relation to art. Tim Davis’s series Colosseum pictures, which depicts the screens of several digital cameras showing images of the infinitely reproduced landmark in Rome, captures ‘a very particular moment in the history of digital photography, just before smart phone cameras’ FIG.8.14 Antonio Pérez Rio’s series Masterpieces from 2014–18 captures smart phones being used to take photographs of famous paintings, perhaps with a view to sharing these on social media FIG.9. Claudia Angelmaier’s Blauracke depicts several books containing reproductions of the same work of art, revealing stark differences in colour and quality FIG.10. Much like Levine’s photographs, Angelmaier’s series demonstrates photography’s dual relationship to art: ‘on the one hand, it can be an art in itself, expressive, subjective, inventive. On the other, it can be the means by which all the other visual arts—from painting to sculpture, to performance and site-specific art (such as Land Art), can be documented, reproduced, publicized, and disseminated’.15

Most importantly, Angelmaier’s photograph reveals the effect of taking these individual images out of context, the various books they were originally published in, and gathering them in one place. Perhaps it is no coincidence that this work is displayed in earshot of Adams’s video, in which an exasperated Malraux complains about ‘biennial culture’, which is about everything except the art itself. One can’t help but think that by gathering photographs in a museum or gallery something of the medium and its function in the world, the innumerable lives it lives are lost.

Due to the continuing spread of the coronavirus in Germany, the biennale is closed to the public until further notice. All six exhibitions can be visited here in digital form.