Helen Marten

by Rebecca O’Dwyer

Reviews /

Exhibition

• 19.02.2019

Fixed Sky Situation at König Galerie, Berlin, is Helen Marten’s first solo exhibition since winning the Turner Prize in 2016. This surprisingly long period of inactivity obviously stems from a decision rather than any lack of opportunity. The press release takes pains to explain this seeming gap in productivity: Marten, it assures us, spent 2017 working on her forthcoming novel, The Boiled in Between. Fixed Sky Situation, a staggering, sprawling and complex body of work, is itself a kind of novel: a world that we are invited to enter, but one in which individual details demur to recede or even to sit still.

Installed in the gallery’s huge main space – in what was, at an earlier point in time, the nave of the brutalist St. Agnes’ Catholic church – the exhibition contains eight new works, all made in 2018. Five large silkscreen prints are hung on the gallery walls, alongside three meandering and intricate sculptures that spill out over two levels of the considerable floor space. In the opening weeks of the show, viewers were free to approach and walk around the sculptures, but a series of typed warnings were later set out on the floor, instructing visitors to stay back. This is a problem, because the exhibition’s real value is found in details only encountered by getting extremely close. To be with Marten’s work is to peer into small alcoves and nooks, or crouch back on our heels for underside views. It is an exhibition of almost excessive detail and materiality, requiring a careful, embodied reading. At times, its surfeit is almost overwhelming.

The sculptures are identified as three individual works, beguilingly referred to as ‘them’, ‘us’ and ‘you’. On entering the nave, the first work, A bath in italics (you) FIG.1, is installed in the centre of the gallery. A characteristically multifarious arrangement of objects: in the middle is something that resembles a kitchen island, its limits marked by a chute resembling a slide or some component of manufacturing that meets the ground at a steep angle. Jugs, dishcloths, scraps of fabric, drawings, a telephone book, lumps of copper: each of the numerous surfaces are utilised, with objects – such as the Imperial Leather soap bars stashed in what looks a bit like a sink – admitting the appearance of things that were meant to be functional but got stuck somewhere along the way. Objects are like text, turned or italicised. Almost objects, very nearly domestic, almost a kitchen. Marten looks to objects that ring out with prior association.

To enter into Marten’s awry, vaguely homely spaces is to look for clues. Every detail has the possibility of taking on significance, and with this, of altering the viewer’s relation to the whole. The two works in the main gallery space, Water fidelity (them) FIG.2 and People, terms in barking (us) FIG.3 are closely related. The first, them, is a kind of discombobulated hut standing taller than head-height; the same mechanical, chute-like addendum extends out from one of its sides, creating an enclosure of sorts. Beside a small pile of twigs, a sign on one of the hut’s sides reads ‘host’, while another, elsewhere, reads ‘service’. Moving further down the gallery space, a large dividing wall announces People, terms in barking (us). Resembling a shop display, or a carpenter’s bench in the process of disassembly, it stretches languorously over the floor, encircled by six satellite forms. The configuration invites a closer look, and we approach the bench and peruse as we would in a shop. Moving up closer, we see spent tea bags, strange ceramics and lots of eggs. Is this a means of constituting a self?

All the sculptures here – us, you, and them – share a kind of language: motifs, such as a snake, recur over each of their multi-planar surfaces, and all are made in much the same way, via a combination of handmade and readymade objects. The work here is defined by a warped domesticity. Colours are broadly pastel and tasteful, calling to mind the middle-class interior design shops that, alongside ceramic homeware, kitschy trinkets and plaques with inspirational quotes, aim to endorse a particular narrative or means of understanding the self’s relation to the world. But any narrative here is incomplete; the sculptures’ severed chutes suggest the works are only minor, disconnected segments hewn from something that far exceeds the gallery space.

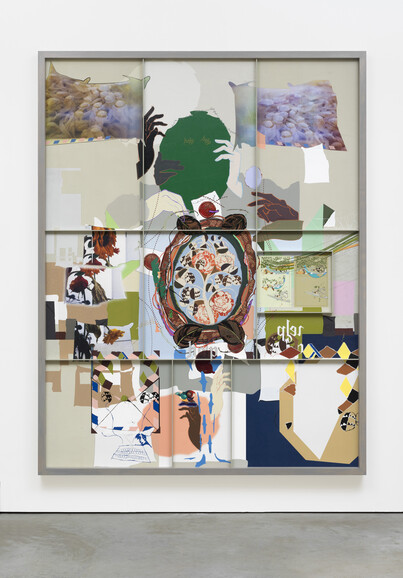

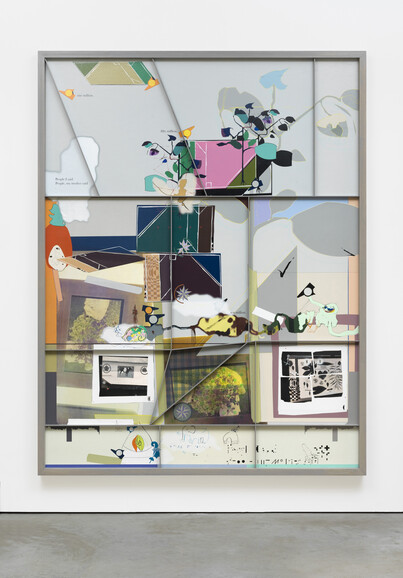

This prioritisation of the detail is carried over in the five vivid silkscreen prints, referred to in the press release as ‘chapters’, which have a language of their own, each seeking ‘to trace the snaking fever of a body’s pulse’. Large and monumental, these works loom over the sculptures below but are less successful, behaving more like illustrations of the sculptures’ activity. Images overlay one another – some elements seem to refer to Japanese prints, while others recall stock images FIG.4. Text makes its appearance with snippets of prose or conversation FIG.5 emerging from the digital ground. These are strange hybrid things; while redolent of contemporary digital techniques, the details in these prints are neither slick nor flat: they stay distinct from each other, much like those that punctuate the structures of the sculptures alongside.

Throughout, Marten exaggerates the detail, making each seem intensely self-enclosed and disconnected from the larger whole, just as in novels where details can emerge and take on a strange life of their own as we remember them long after the outlines of the story have faded. In the short accompanying text that lends the exhibition its name, Marten refers to the film Powers of Ten (1977) by Charles and Ray Eames, in which a picnic is tracked in a sequence of aerial shots, starting close-up before pulling all the way back to space. The mise en scène of Fixed Sky Situation can be thought, as Marten writes, as ‘a materially more abject version of that picnic’. The fragmentation and dislocation of the sculptures is not, however, the consequence of moving outwards but of moving in closer. Awkwardly charged, Marten’s objects refuse to renege on their individual specificity. Details keep a strange pulse of their own.